"We Make People Happy" Part 4

Stories built Baskin-Robbins 31 Ice Cream. Stories of 31 Flavors in an age of commoditized supermarket brands. Stories that brought individual flavors to life, giving them personality and character. Stories of new flavors introduced each month that kept word-of-mouth buzzing. Stories told in the stores by amusing signs, free samples and (always) that array of 31 Flavors front and center.

In its first three decades, Baskin-Robbins constantly told stories. But there was one story that was the story.

"We don't sell ice cream," Irv Robbins once said. "We sell fun!"

He was wrong, of course. Baskin-Robbins did (and does) sell ice cream. The company produced it and sold it to franchisees who sold it to customers. Customers came to Baskin-Robbins stores to buy ice cream. That was the revenue stream, the way things worked. Everyone knew it, from Mr. Robbins to millions of customers.

But that's not what they believed.

Seth Godin says All Marketers Are Liars—and if we want to get technical, Mr. Robbins was lying too. But check Godin's money quote:

And here's the Big Secret: The Baskin-Robbins story worked so well because it was true. People did have fun at Baskin-Robbins. Children—the world's biggest ice cream fans—enjoyed the desire, the discovery, the deliberation, the denouement provided by that first lick. Parents enjoyed their children's delight, the ease of service, the kid-friendly environment and a little treat for themselves. Adults enjoyed the novelty, the grown-up flavors and the feeling of being in-the-know. Seniors enjoyed echoes of days past, memories of soda fountains and personal service.

Godin notes that great stories are true—not necessarily because they're factual but because they are "consistent and authentic" and don't contradict themselves. Baskin-Robbins met the challenge.

One key reason was that in its early decades the organization was small enough that there could be just two degrees of separation between its founders and the workers on the dipping line. Mr. Baskin and Mr. Robbins personally transmitted their passion and obsession to each franchisee. (Indeed, the first franchise agreement required that the store be operated "in the same manner and on the same principles" as Mr. Robbins had.) In turn, storeowners passed them to their employees who delivered the promise day after day. Further, a flow of communications from headquarters kept franchisees and employees alike in the loop. Thus the brand story spread directly from the enthusiastic source to customers eager to believe it.

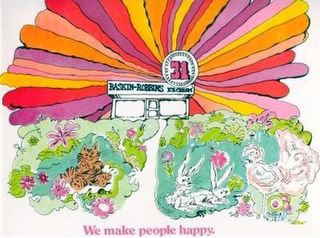

One more story for today. Perhaps the quintessential expression of the Baskin-Robbins story of fun emerged in the early 1970s during a cloudy transatlantic flight. Marketing VP Bruce Enderwood (a master marketer and enthusiastic storyteller) was musing over potential marketing strategies in his window seat when the plane broke through the clouds into a brilliant blue sky. Inspiration struck! Mr. Enderwood reached for an airsickness bag and wrote this rendition of the Baskin-Robbins story:

After 25 years of meeting its promise, the company had earned the right to proclaim it.

Next time: The day the story died.

In its first three decades, Baskin-Robbins constantly told stories. But there was one story that was the story.

"We don't sell ice cream," Irv Robbins once said. "We sell fun!"

He was wrong, of course. Baskin-Robbins did (and does) sell ice cream. The company produced it and sold it to franchisees who sold it to customers. Customers came to Baskin-Robbins stores to buy ice cream. That was the revenue stream, the way things worked. Everyone knew it, from Mr. Robbins to millions of customers.

But that's not what they believed.

Seth Godin says All Marketers Are Liars—and if we want to get technical, Mr. Robbins was lying too. But check Godin's money quote:

Marketers aren't liars. They are just storytellers. It's the consumers who are liars. As consumers, we lie to ourselves every day. We lie to ourselves about what we wear, where we live, how we vote and what we do at work. Successful marketers are just the providers of stories that consumers choose to believe.The story Baskin-Robbins told for its first 30 or 40 years was that it sold fun—and people believed it because they wanted to believe it. Godin continues,

Stories let us lie to ourselves. And those lies satisfy our desires. It's the story, not the goods or the service you actually sell, that pleases the consumer.People want to have fun and the Baskin-Robbins story told them they could have it under the sign of the Big 31.

And here's the Big Secret: The Baskin-Robbins story worked so well because it was true. People did have fun at Baskin-Robbins. Children—the world's biggest ice cream fans—enjoyed the desire, the discovery, the deliberation, the denouement provided by that first lick. Parents enjoyed their children's delight, the ease of service, the kid-friendly environment and a little treat for themselves. Adults enjoyed the novelty, the grown-up flavors and the feeling of being in-the-know. Seniors enjoyed echoes of days past, memories of soda fountains and personal service.

Godin notes that great stories are true—not necessarily because they're factual but because they are "consistent and authentic" and don't contradict themselves. Baskin-Robbins met the challenge.

One key reason was that in its early decades the organization was small enough that there could be just two degrees of separation between its founders and the workers on the dipping line. Mr. Baskin and Mr. Robbins personally transmitted their passion and obsession to each franchisee. (Indeed, the first franchise agreement required that the store be operated "in the same manner and on the same principles" as Mr. Robbins had.) In turn, storeowners passed them to their employees who delivered the promise day after day. Further, a flow of communications from headquarters kept franchisees and employees alike in the loop. Thus the brand story spread directly from the enthusiastic source to customers eager to believe it.

One more story for today. Perhaps the quintessential expression of the Baskin-Robbins story of fun emerged in the early 1970s during a cloudy transatlantic flight. Marketing VP Bruce Enderwood (a master marketer and enthusiastic storyteller) was musing over potential marketing strategies in his window seat when the plane broke through the clouds into a brilliant blue sky. Inspiration struck! Mr. Enderwood reached for an airsickness bag and wrote this rendition of the Baskin-Robbins story:

We make people happy.

After 25 years of meeting its promise, the company had earned the right to proclaim it.

Next time: The day the story died.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home